Back around the time that I enlisted in the Marines, I came to an abrupt realization: very little fiction featuring or focused on the military actually reflected what I saw as the reality of the military. For the most part, what I saw was a lot of people behaving in ways unrealistic for their roles, particularly in that commissioned officers were badass, all-purpose action heroes. Junior enlisted (a/k/a the numerical bulk of the military) featured not at all, or if featured slotted into convenient stereotypes, and if a story started with focus on a private, you could bet a paycheck or two that he or she would wind up some kind of commissioned officer (lieutenant, captain, etc.) by the end of the story.

Back around the time that I enlisted in the Marines, I came to an abrupt realization: very little fiction featuring or focused on the military actually reflected what I saw as the reality of the military. For the most part, what I saw was a lot of people behaving in ways unrealistic for their roles, particularly in that commissioned officers were badass, all-purpose action heroes. Junior enlisted (a/k/a the numerical bulk of the military) featured not at all, or if featured slotted into convenient stereotypes, and if a story started with focus on a private, you could bet a paycheck or two that he or she would wind up some kind of commissioned officer (lieutenant, captain, etc.) by the end of the story.

This is purest, refined, high-quality, premium-grade horseshit. This never happens. The closest it got to being a thing was in World War II, due to the sheer scale and attrition of that war.

Yes, officers definitely get their heroics in, though usually it’s alongside lots of lower enlisted folks, often committing heroics on a similar scale. But for the most part, their job is to direct and supervise everyone else doing the actual fighting.

But if you read a lot of military fiction, especially science fiction, you’d get the impression that only officers had stories to tell, and they were the only ones who could interest and engage an audience. I get that part of this is due to the “big picture,” in that an audience (allegedly) feels the need to see the entire scope of the conflict and the character’s part in it. I would argue, however, that there are ways to communicate big picture through a junior enlisted character (who remains junior enlisted), and that big picture is not necessary to tell an engaging story.

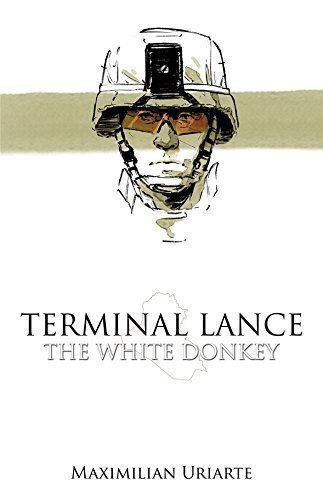

Terminal Lance: The White Donkey is as close as I can get to a thesis on this particular topic, at least for now. The graphic novel was written and illustrated by Maximilian Uriarte, a former Marine infantryman and veteran of Iraq (like me!), who created this project as a Kickstarter back in 2013. By then, he’d been at work on a sort-of companion webcomic, Terminal Lance, for three years, starting in 2010 just before he got out of the Marines. After some delays, he finally dropped the book to backers, plus a supply for general purchase on Amazon, this past Monday.

The story follows Abe, a disgruntled junior enlisted Marine as he prepares for, then departs for the war in Iraq, circa 2007. His experiences there are personally problematic, and his disgruntlement spills over in dramatic ways. Along the way he experiences things both surreal and illuminating, and provides a lot of commentary not only on the Iraq war specifically, but war and warriors in general. Unsurprisingly, given his experience, the other junior enlisted Marines are drawn (figuratively and literally) like real people, not two-dimensional placeholders.

The best comparison to this is probably the Oliver Stone movie Platoon, which like The White Donkey, draws from the creator’s own experiences in a hard and unpopular war, with educated protagonists seen as working “beneath” themselves by enlisting in the infantry with the idea of going to war. There are specific incidents that draw from real life, and the war is portrayed as it is (for the most part) with very little hype or stylization. The junior enlisted characters never really advance in rank, they have conflicts with authority, and they’re searching for some meaning beyond themselves. They both find it in the end, though that really is the sum of the similarities in the stories.

Platoon features an arc that is generally too convenient for real life, and Stone is known to have mashed together things that happened to other units or (in the case of the climactic call for a bombing run right on the unit’s position ) to other services. But that is part of the requirement of the story he was telling, in the war movie format. Uriarte had more latitude, being a creator-published work, and the story he wanted to tell was different, incorporating the return from Iraq and dealing with the effects of what happened there. And he executes it well, beginning to end, in every facet of the medium.

Bottom line, excellent book and another datapoint for my thesis: small scope stories have merit, junior enlisted stories have merit, and they’re often more true to the realities of conflict than stories that focus on officers and senior enlisted.

—

Unfortunate footnote: you can’t get the book any more. The author sold through his print run of the book, and seems disinclined to foot the bill for another printing on his own. I’m hopeful he find a publisher for it, but it may be seen as too niche for a traditional publishing deal. If I know you well and you want to borrow it, something can be arranged, but for now… it’s a rare bird.